December’s already a hard month of waning light and dwindling days without adding the anxiety of elbowing my way through frantic shoppers or digging myself into debt. With so little daylight, staying cheerful in December is difficult enough, even without the anxiety of crowds and commerce. And when there’s no snow, December is that much harder, shutting me up indoors to brood.

In the past, I’ve fallen prey to year-end dissatisfaction by enumerating the tasks I failed to accomplish instead of acknowledging all the goals I’ve met. I’ve made myself miserable so often in December, that I’ve started developing strategies to keep me out of the Slough of Despond. And I’m glad to say that these strategies seem to be working.

Not shopping is one of the best, By giving gifts from the garden (last week’s post), I’m absolved from shopping. I’m not one to drive to a mall or shop in a big box store in any circumstance, and certainly not between Thanksgiving and Christmas, when just the thought of Muzak and fluorescent lighting can trigger a migraine. Instead of buying gifts in December, we’ve started a tradition of visiting museums.

Vermont is rich in museums, and we live within an hour’s drive from several in neighboring states. In fact, I live closer to more museums than the nearest mall. And this time of year, when the food courts are full, we have the galleries nearly to ourselves.

So far this month, I’ve seen two splendid exhibits at two different museums. Shedding Light on the Working Forest is a collaborative exhibit of paintings by Kathleen Kolb and poems by Verandah Porche, currently at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center, and Sol LeWitt, a Wall Drawing Retrospective, at Mass MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts.

BMAC is my splendid, hometown art museum that regularly mounts remarkable, outsized, shows in its modest space – a former train station. Mass MoCA is located in a vast, former industrial mill where it occupies only a few of the many buildings, which are themselves art and artifact.

Both these exhibits opened my eyes in new ways. Shedding Light on the Working Forest showed me how the woods aren’t just scenery, nor only a place to escape for recreational purposes. They are a natural resource of tremendous economic significance as well as a source of natural beauty, and there’s a cadre of people who harvest the lumber we take for granted in our daily lives: My wooden house, pine desk, oak dining table, cherry bed, and – of course – the firewood that we split and stack from June to October and burn from November through May.

Kolb’s stunning drawings and paintings honor the loggers and sawyers at work in the woods by bringing the viewer right into the scene with intimate detail. But it’s the light of dawn and dusk and mist, of fall, winter and early spring, which illuminates both the majesty of the trees and the dignity of the work.

Poet Verandah Porche interviewed the subjects who appear in the painting and retells their stories in what she calls “told poems.” This narrative technique allows the stories to sing in the subjects’ own voices, and to amplify the poetic light and tension of the paintings, just as the paintings illustrate the poems.

But the exhibit does more: it amplifies how interconnected we are: artist and poet, viewer and reader, logger and wood, Vermonters and landscape. This exhibit fulfilled one of the missions of art: it changed how I see the world.

(Deborah Lee Luskin, photo)

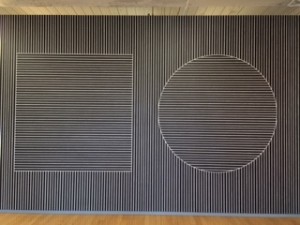

So did the Sol LeWitt exhibit at Mass MoCA, where his giant wall paintings span three giant floors, from his earliest work in the 1960s to conceptual pieces that have been painted posthumously for this exhibit.

As a writer, I’m often text-bound. I’m most comfortable with black on white blocks of text, and I overlook images in favor of words. LeWitt’s wall paintings helped me break free of that.

For one, his early work is all about lines, and I loved the possibilities, nearly mathematical, with which he created quilt-like arrangements of them: horizontal, vertical and diagonal, both left and right. These early works are very much like Bach’s two-part inventions, some of which I once knew how to play and to which I still listen.

(Deborah Lee Luskin, photo)

In mid-career, LeWitt’s lines ballooned into great stripes of color and geometrical shapes. Some of the color combinations were painfully bright, and the shapes bold, but never simple. The mathematics changed, too, so that flowing patterns were repeated at varying frequency. I enjoyed puzzling out the shifts and changes, and started seeing patterns in the bricks and beams of the industrial building where the paintings hang.

In some of the stunning late work, LeWitt returned to a monochromatic palette: an entire wall of black on black: matte and glossy waves undulating across the wall.

I left these galleries satisfied with looking, seeing, thinking – replete, satisfied – and grounded, happy, enlarged. Back home, I’m ready to start baking and making gifts for friends, along with notes of gratitude and love.

(Deborah Lee Luskin, photo)

Wishing all my readers light and love as we tunnel into the dark of the year.