A sentence is a complete thought, containing both subject and verb. The subject is what the sentence is about, and the verb is what the subject is doing.

A sentence is a complete thought, containing both subject and verb. The subject is what the sentence is about, and the verb is what the subject is doing.

Here’s an example of a sentence: I write.

“I” is the subject, and “write” is what I do.

Simple as that. (“Simple as that” is not a complete thought; it’s a sentence fragment, the sort of thing your English teacher would murder with red ink, but which creative writers can get away with when they know what they’re doing. “Simple as that” has neither a subject nor a verb. It’s a modifying phrase, and phrases aren’t sentences at all; they’re not even clauses.)

Sentences come in several varieties determined by the kind and number of the clauses it contains.

A clause is either independent, containing both a subject and verb of its own, or dependent, meaning it has to lean on an independent clause to make sense.

The Simple sentence is comprised of a single, independent clause, like “I write.”

A Compound sentence contains two or more independence clauses: I write, and I walk the dog. (Two independent clauses joined by the coordinating conjunction “and.” The other coordinating conjunctions are but, or, for, nor, so yet.)

A Complex sentence is made from a dependent clause and an independent clause: When I can’t write, I walk the dog. (“When I can’t write” is a dependent clause; “I walk the dog” is the independent one.)

A Compound-Complex sentence uses one or more dependent clauses with one or more independent clauses: While I’m writing, my dog sleeps under my desk, but even when we’re out walking, I’m still sifting through words and sentences, thinking about the work I left on my desk. (This sentence has two independent clauses: “my dog sleeps under my desk” and “I’m still sifting through words and sentences,” and it has two dependent clauses: “While I’m writing” and “even when we’re out walking.” Additionally, it has the adverbial phrase, “thinking about the work I left on my desk,” which describes how the subject of the sentence is walking.)

“This is all very interesting,” you’re saying to yourself, “but what does it all mean?”

When you know how a sentence works, you have a better chance of writing an effective sentence.

An effective sentence uses unity and logical thinking. “I write, therefore I am” is both unified and logical. “I write and tomorrow I have to return a book to the library” is neither unified nor logical – even though it’s true.

A good sentence uses subordination effectively. Put another way, a good sentence puts what’s important in the independent clause, and tucks all the other stuff elsewhere.

- “After breakfast and before lunch, I started another revision of my novel.” Written this way, “I started another revision of my novel” is the important part of that sentence, and everything else is a prepositional phrase that embellishes the main thought.

- “Even though I started another revision of my novel this morning, I didn’t miss either breakfast or lunch.” In this sentence, eating is more important than writing. Some days are like that.

Coherence is another quality you want in your sentence. A sentence, which is a thought with a subject and verb, should stick together in a way that makes sense. Coherence depends on word order, which you can learn about in my post, The English Language on Word Order Depends.

Parallel structure is another nifty tool, especially if you want to write sentences that are long, elegant and euphonious. The previous sentence demonstrates one type of parallel structure; there are others.

In fact, parallel structure deserves its own post, as do Emphasis and Variety. Stay tuned.

Deborah Lee Luskin is a novelist, essayist and educator. She lives in southern Vermont.

I used to LOVE writing compound complex sentences and then diagramming them, just for fun. My English teacher said I was seriously disturbed…but they were always correct LOL 🙂

Hi Morgan,

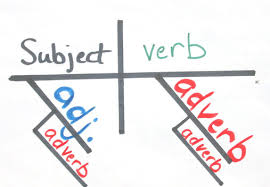

Diagramming sentences is an excellent way to learn both parts of speech and sentence construction. Is it taught any more? I’m not sure. My kids did some diagramming when they were in fifth grade – but that they’re all out of college now, so that was a while back.

Thanks for commenting,

Deborah

I am not sure if they still teach it or not, sadly.

Where are taught they still teach it!

Where we are from, they still teach it! ha sorry!

Thank you for that. While on the subject of grammar, i have been pondering over this construction and would appreciate an explanation. From Jhumpa Lahiri’s, Lowland….”He’d watched from the street, standing among the bettors and other spectators unable to afford a ticket, or to enter the club’s grounds.”

Why he’d and not he? A contraction for he had? Sorry, no verb!

Yes, the verb is in the contraction, he’d (he had). This is a form of the past, the past perfect, I believe. “He’d watched from the street” is the independent clause in this complex sentence, where everything that follows describes his condition as he watched: standing . . unable to afford . . to enter.

Does this make sense? Can anyone else out there explain it better?

Thanks for your query,

Deborah.

The subject was covered in your article today was quite refreshing. I rely upon Microsoft’s word 2010 so that my grammar is not in the kitchen feeding the cat.

My two greatest enemies are passive sentences and sentences too long. Writing a narrative or a novel one has to be like an artist painting a picture, often I find it hard not to be caught in the passive trap. Especially writing poetry the temptation not to make a sentence too long destroys the complete thought of the verse. I have two questions that need to be answered so my poems do not lose rhythm.

Is it proper to use a period in the middle of the verse?

My second question is that of all the great classic poets that we read about in school broke every grammatical error in creating classic poetry. Do I sacrifice grammar as they did in writing verse or do I strive to stay within the bounds of today’s vernacular phrases. Reading Emerson’s essay’s I often have to reread certain passages to get the essence of what he is saying due to the style of his writing of which I think is very profound.Sometimes I find myself entrapped in a fragmented sentence however I enjoy the pleasure of escaping a fragmented sentence because the procedure benefits my poetry.

After reading my published book I found that I used commas in the wrong places because it sounded as if I was using a run on sentence when I listened to the dictation as read in my MS Word 2010. Please enlighten me of avoiding these traps when writing poetry.

Thank you

Terrance Tracy

A badly needed refresher course.

One way to acquire a sense for long sentences is to read classical literature out loud. The sound and rhythm of sentence structure is somehow absorbed and reappears in your own original writing. (with a few new vocabulary words as a bonus)

Poetry? Now that’s a whole different animal….Concise. Precise. Best words in the best order by the best minds?

Yes! Yes! Yes!

The Victorians, famously, were influenced by the reading aloud of the King James Bible, which resonates with beautiful long sentences.

And spot on about poetry.

Thanks for adding your comments here.

Deborah.

Hi Terrance,

I agree with you that passive voice is often the enemy of good prose. It’s easy to fix: make sure the subject is performing the action. (As in my first sentence, “I agree.”) I’ll put the topic of active/passive voice on my list of topics for future posts. In the meantime, you might simply google “passive voice” and see what you can learn about recasting sentencing into active voice.

As for overlong sentences – I’m not the one to ask! I love long sentences, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with them as long as the main idea is paramount, with everything else subordinated in dependent clauses and properly placed modifying phrases. (That last sentence is an example.)

Asking questions and studying craft are good ways to learn about how to control language rather than have language control you.

Thanks for being in touch,

Deborah.

Thanks for the post. I often struggle to keep my sentences short, simple and crisp!

Your comment has great rhythm – so clearly, you know what you’re doing.

Thanks for commenting,

Deborah.

I love this and found it very helpful. Being educated in 80s and 90s Australia when grammar was out of vogue, so much of my writing is instinctual. It is wonderful to see sentence structure explained so clearly!

Glad you found this helpful!

Grammar out of vogue? Never!

Can writers get away with starting a sentence with but. I’ve seen that.

But of course!

I am practically drooling over this post, sentence diagrams are like chocolate for me. thank you so much!

Thanks for reading and commenting on Live to Write – Write to Live.

Deborah.

As a non native speaker complex sentences in English are super difficult. They easily look weird 🙁

English is a difficult language even for native speakers, so power to you for learning it! -Deborah.

Thank you for your reply. I will endeavor to take your suggestions seriously.

My passion for poetry is inspired by the King James Bible. Ninety-eight percent of my poems are poems that surround a particular Scripture. I do not take Scripture out of context to make an ideological pretextual interpretation. I simply use the Scripture as an inspiration for poems that come from my heart.

One may read the Bible simply as Scripture however, I have found that reading the Bible as poetry is very rewarding especially when one reads the passage with the implied emotion; the Holy Spirit will give you an ear to hear with understanding the truth as written.

Terrance Tracy

… with a subject and verb, should stick together in a way that makes sense.

Sorry’ excuse my asking, but shouldn’t that have been,…that should stick together.

please excuse my uneducated question, (just learning ) thanks.

Alex,

Asking questions is a great way to learn!

The sentence you’re questioning is, “A sentence, which is a thought with a subject and verb, should stick together in a way that makes sense.”

“which is a thought with a subject and verb” is a relative clause, describing “a sentence”. This clause, set off by two commas, acts as an appositive and can’t grammatically take a relative clause such as the one you propose, “that should stick together” which is also a relative clause, but of another kind.

I’ll put the use of relative pronouns and relative clauses on my growing list of subjects to consider in future posts.

English is complicated – and changing. Thanks for your comment. Hope this helps.

Deborah.

Reblogged this on and commented:

A few clear instructions on proper sentence structure!

Saya banyak mendapat pelajaran berharga disini.

Terima kasih..

Such a helpful post with clear instructions accompanied by sentence diagrams.

Thanks

Sayori