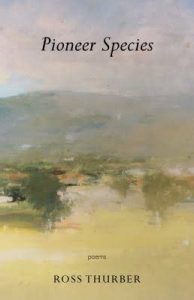

Poet Ross Thurber describes the publication of Pioneer Species, his first collection, as his “coming out” as a poet, of sharing his world-view in his private language of images gleaned from his daily life on Lilac Ridge Farm.

Ross is clear that farming Lilac Ridge, a small, organic dairy farm in West Brattleboro, Vermont, is a collective, multigenerational, community-supported effort.

His poetry is entirely his own.

The poems follow the agricultural year with the precise observation of a man who spends his days tending the land at a working pace. Their slow rhythm mimics walking across the landscape in the liminal hours of dawn and dusk, and their language reveals the intimacy of knowing a particular place in all seasons, all weather, all hours.

Reading Pioneer Species is the distillation of a year on the farm and the discoveries of meaning found in metaphor, repetition, and nature – nature found both outdoors and within the human heart.

Essential Solitude

When I visited Ross one recent morning, he talked about an essential solitude of which he was self-aware by middle school. He wrote his first poem in eighth grade. Clearly, this is an existential solitude, separate from the three generations he lives with, or the community in which he is embraced.

At about the same time as writing that first poem, people began asking if Ross was going to take over the farm.

Ross says, “Even though dairy farming was decently profitable in the 1980’s, it had no cultural cache, no social capital.”

In his teens, Ross was pulled by both sports and the arts, not farming, and after high school he headed west. It was there where he first heard the term, “sustainable agriculture.”

He returned to Vermont and enrolled in UVM’s school of agriculture. Outwardly, he was studying the economics and practices of organic dairy farming. Privately, he was reading literature, auditing English classes, and reading Wordsworth, Dylan Tomas, Robert Frost, Jane Kenyon and Tomas Transtromer on his own.

Also at UVM, Ross met Amanda Ellis, a plant and soil scientist. They married and returned to Lilac Ridge, where Amanda added organic strawberry and vegetable production to the milk and maple syrup operations at the farm.

Ross confesses the first decade after taking the farm organic, expanding the vegetable production and sales, inviting school children to learn about soil, plants, and farming, and having their own three children kept them busy. And he credits Amanda for pushing him out the door at the end of the day to attend poetry readings.

“Amanda’s outgoing,” Ross confesses. He’s quiet – easily mistaken for shy – draped in the solitude where poetry rises.

“Poetry’s an imperative,” he says, “and I started writing in 2007, when Suzanne Kingsbury started her writing salon.”

That’s where I first met Ross, who pulled images he’d collected outdoors onto the page, creating poems that juxtaposed observations of the natural world with specific, human experience.

The Poems

Pioneer Species refers to the first trees to walk into a clearing and take root. The book is divided into four sections, each one related to a season: Green Popplewood (Spring); Sunburnt Juniper (Summer); Stag Horn Sumac (Fall); Snow Melt, Black Brook (Winter).

In the opening poem, Ground Truthed, the speaker describes himself:

I am a poor king; bird on a branch,

stone picker, woodsman, herdsman

My stables small, my fields flinty

pitched and far from the river.

But the final stanza refutes the poor king’s poverty by describing the spiritual wealth available to one who can,

Give up your grip, let down the floodgate.

The middling mountains will hold

your silt, wing flaps, meanders,

passing concerns.

Many of these poems rise from the solitude of farm life, from rising before dawn to milk the herd, to the evening walk across a pasture to fetch them back to the barn.

In Wintering Grounds, the speaker narrates the farmer’s cares on a below-zero night. This poem is filled with tropes and word play of flight, from the “pre flight check” to the blue light of a neighbor’s TV that “flickers like a pilot light.” We worry with the narrator throughout the freezing night, accompany him through the “vacant” morning, when “It’s too cold for much else besides verification.” And we’re as startled and delighted at the end of the poem, when the narrator unplugs the tractor’s engine heater, “and four English Sparrows, perched on the fuel lines/quickly, trance like, take flight.”

This is the startling miracle of life even during the dark, coldest hours of winter.

Thurber shows us something entirely different in The Cows Are Walking Through the Forest, when the speaker heads out through morning fog to bring the cows in from “this old arable/hoof worn hill drenched with dew.” The speaker has set the pre-dawn scene of a cool early morning in summer, and ends with an image of summer’s brute strength.

The cows are walking through

The forest leaving a trail of crushed

Needles before entering the maw

Of a heavy summer day.

Music

There is remarkable music in these poems, as well as detailed images harvested from the Vermont landscape. In Bell Foundry, the line “I’m giving up the torch for a bell,” tolls for the end of winter and the coming of spring, and “makes the dew lapped/sounds of poems when you wake.”

In Blue Notes, Thurber creates in the rhythm of language, the jazz of haying a field, from the golden horn that holds the grass spellbound, to the chortle of the tractor’s fuel pump, culminating in evening, which “follows the rhythm section and trickles in.” The sounds, heat, effort, and thirst of haying fade as night falls, and “A fox with one sable leg arrives at dusk, cases the meadow/Stays until closing time.”

Taciturn April

Perhaps because this collection was published during a particularly taciturn Vermont April that spat snow right through the third week before turning green and gold, that I find the poems in the first section so moving, as in Easter Blues, which begins, “The good news has yet to reach us/out here in the stale wood,” and ends,

I would like to start again

back at dawn. Look east.

Remember you are rising too,

and stop searching

for the living among the dead.

This is a collection to read in all seasons, and to refer back to for music, language, and the mysteries revealed through compression, juxtaposition, imagery and ideas that are the hallmarks of well-crafted poems husbanded in deep loam.

Thank you so much for sharing this poet, Deb. I just arrived at my Chester house tonight, am sitting on my deck listening to the sublime chorus of spring peepers along the Williams River behind my house. You write so eloquently of the poet’s discoveries in solitude. I can’t wait to read his poetry. I’ve been working on my own poetry for almost two years now, which is inspired by the gift of solitude I’ve found in these Vermont hills. Anyone you can direct me to in the realms of poetic expression here in Vermont I’d appreciate immensely. Any poetry plans for the writing circle this summer?

There are two poets reading tomorrow evening at the Book Lounge in Brattleboro: Michael Fleming and Baron Wormser. And you’re always welcome to write poetry to the prompt in Writing Circle. It’s under just such circumstances that both Ross and Michael compose, while those of us with clay pens write prose. Welcome back to Vermont!

Thanks so much. What are the dates for writing circle

What a gorgeous review. Your description of Ross Thurber’s early awareness of his own solitary nature reminds me of the opening of P.L. Gaus’ novel “Blood of the Prodigal,” in which a young Amish boy steals time in the morning to be by himself (not an experience sanctioned by his community or his family).

Thank you.

Thanks for making this connection for me, Fran. I think poetry provides the solitude we all need but don’t always allow ourselves.

And I ordered a copy of the book on the steength of your review. Thanks again!