As a child, summers seemed endless. I played hopscotch, tag, and running bases with the kids on my street, and I spent two timeless weeks at the beach with my family, where I was toasted by sun and tumbled by waves. The season’s good weather and expansive leisure was interrupted by occasional bouts of boredom that we overcame by riding our bikes to the library or walking to the candy store, where deciding how to spend a quarter could take hours. We ended each day with reluctance, after capturing fireflies, taking a forced bath, and reading before bed.

While each day differed slightly one from the other, the only way to tell that the days were accumulating toward an eventual end was by the degree that my Keds faded and frayed. School seemed theoretical even at the store where a man knelt to measure my feet for shoe leather, and I was surprised the day my mom laid out a new jumper and said, “School starts tomorrow!” How did she know? I didn’t believe her until I met my playmates all similarly scrubbed and crowding the sidewalk toward school.

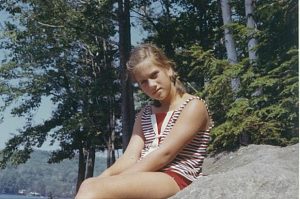

The rhythm of school days was my first lesson in marking time, with names of the days punctuated by predictable weekends. Holidays and birthdays still arrived at enormous and seemingly unpredictable intervals, like magic. But time changes as we age, and I distinctly remember the moment I discovered summer was finite. I was about twelve, visiting my aunt and uncle at their summer home.

We were heading down to the general store, and just where Timson Hill makes a sharp curve, I turned to Uncle Dave and said, “Summer’s only twelve weeks long. It goes so much faster now that I’m old.”

He nodded. He was a schoolteacher in New York City and arranged his life around those twelve weeks, which he spent in Vermont. In my late twenties, I followed suit and came to Vermont for a summer during graduate school, which lasted from May through August. Four months still wasn’t long enough, so I stayed.

It wasn’t until I lived in Vermont year-round that I became aware of summer waning the moment it starts. The solstice arrives before the hot weather kicks in, and daylight begins to dwindle even before the strawberries are ripe. While hot weather will arrive in July and August, so does the dark, so I’ve had to find other ways of making the most of summer time.

One way is to rise early, when the sun slants low across the meadow. Another is to spend as much time as possible outside, even writing with pen and paper supported on the arm of an Adirondack chair. As often as possible, we cook outdoors and eat our meals on the deck in fair weather, on the back porch if it’s raining, and on the screened porch when the bugs bite. In theory, I’d like to lie out and watch for shooting stars every clear night after dark; in reality, I manage to stay up late enough only once or twice.

As I’ve aged, summers have become shorter, with summer weekends filling up long before the season arrives. Life cycle celebrations, like graduations and weddings, are often inked onto the calendar months in advance, as are visits from family and out-of-town guests. It can be distressing to find summer’s booked by Memorial Day, and easy to feel out of breath before summer has even begun. One of the fortunate aspects of aging, however, is learning how to slow time.

We’ve learned from experience that raising vegetables can’t be rushed and weeds will flourish right along side the beets. So we plant a smaller garden, allocate more time to tend it, and have a more satisfying and successful harvest as a result.

We’ve also learned to limit our home improvement projects, which always take longer than expected. This year, it’s building a stone patio we’ve talked about for almost twenty years, and installing rain gutters to direct water coming off the roof away from the house.

In our younger days, we didn’t pace ourselves so well. For years, we expanded gardens, felled trees, created vistas and talked about how nice it would be to sit and admire the view, but we never allowed time to do so.

Now, we know better.

We’ve learned that one of the best ways to make the most of Vermont’s brief summer is to lengthen each day with deliberation and repose.

Deborah Lee Luskin is the award-winning author of Into the Wilderness, a love story, set in Vermont during the Goldwater – Johnson presidential campaign in 1964. She blogs Wednesdays – Please subscribe: Just enter your address in the box on the right, click “subscribe” and then check your email to confirm your subscription. Thanks.

Wise words, thank you

You’re most welcome! Thanks for reading the blog – and letting me know.