Remembering Ursula K. LeGuin

I never met Ursula K. LeGuin. nor have I read her famous novels.

I have however, read many of her essays, a few of her children’s books, and one very haunting short story.

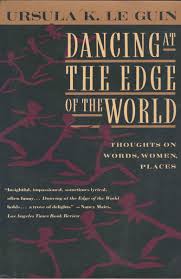

I often to refer to her essay collection, Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places, which I first read when it came out in 1989.

Her essays about the inequities of gender have helped me navigate this man’s world.

In “The Fisherwoman’s Daughter,” LeGuin refutes Virginia Woolf’s argument that in order to write, a woman needs a room of her own.

I’d read Woolf, and I’d followed her advice. I had a room of my own, but it wasn’t enough. With a flexible mind and children of her own, LeGuin helped me understand why. LeGuin says, what a writer needs is a pencil, some paper, and the freedom and responsibility for what she writes with these tools.

Her essay, “The Space Crone,” opens: “The menopause is probably the least glamorous topic imaginable,” and goes on to argue that the ideal person to send into space as a galactic ambassador of the human race is not a nineteen-year old boy, but a mother past childbearing, because “Only a person who has experienced, accepted, and acted the entire human condition . . .can fairly represent humanity.”

LeGuin is imaginative, even playful, in her writing. Her keynote address in 1982 to the National Abortion Rights Action League is a fairy tale. Her children’s books are about kittens born with wings.

While many of LeGuin’s essays are about women, they are ultimately about humanity in which each person, regardless of gender, has equal opportunity. This is never more evident than in her famous short story, Those Who Walk Away From Omelas.

Omelas is a utopian world, or so it would seem. But of course, there’s a catch. In a closet in a basement underneath the gleaming city, a child lives in total neglect. All the citizens of Omelas know about this child because they’re all taken to see it as a rite of passage before they turn twelve. But they are forbidden to speak even a single kind word. The entire utopia depends on everyone knowing that their good fortune is due to this one child’s misery. Those who can’t abide this arrangement, walk away.

There was another essay I read while in graduate school at Columbia. I no longer remember the title of the essay nor the literary journal in which it appeared – just that it was recommended by Karl Kroeber, who was my dissertation advisor and Ursula K. LeGuin’s brother.

The essay was about how humans have been telling stories around the fire since the invention of speech. When the essay was published, people were still reading books, the standard form of shared narratives in the 1980s. Instead of sharing stories around a fire, we were then sharing the same books; books had become our fire pits. Now, of course, we’re sharing memes, posts, news and fake news on-line via the devices that are now our portals to shared stories They’re still stories.

LeGuin understood both the power of story and the human need for narrative. Her influence outlives her in the rich legacy of stories and essays she leaves behind.

A version of this essay was broadcast on the stations of Vermont Public Radio on January 30, 2018. Listen here.

Yes, story telling is so powerful and as you say seems to be inbuilt into our DNA. Your article got me thinking about how much I loved reading stories to or making stories up for my children when they were little; nothing beats having a small one (or several small ones) snuggled up with you while you read them a story. I still remember favourites such as Prince Cinders (a rather neat role reversal) and Little Rabbit Foo Foo (a thuggish rabbit whose chief delight was bopping other little forest creatures over the head – but who gets his come-uppance and becomes a reformed character).

It also made me think about how much I still enjoy listening to stories and plays on the radio – and that I tend to tune in by accident, which means that I am probably missing some great stories that are waiting for me somewhere in a podcast.

Politicians, of course, use stories to sell us a particular strategy or policy and here in the UK the politicians who wanted to leave the EU presented a more compelling narrative, I guess, than their opponents. But they’re now finding out that there’s more to writing a story than thinking up a good title and synopsis – the devil, as they say, is in the detail!

Thanks for affirming the power of story with your story of reading and listening to stories both with others and by yourself. There are so many ways stories connect us to one another: cuddling the kiddos or reading silently and solo. And you’re absolutely spot-on about how politicians tell stories to sway voters. But, as you say, delivering on the promises of those stories is another story entirely!