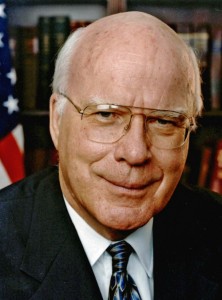

Peter Shumlin is the first native-born governor of Vermont in over thirty years, and Senator Patrick Leahy is the only member of our current congressional delegation born in the state.

The truth of the matter is that a lot of people who were born out of state call themselves Vermonters – and justifiably so. Anyone who lives, works and pays taxes here qualifies, even though people born here will often try to pull rank.

It’s not uncommon for a Vermonter born in-state to stand up at Town Meeting and say, “I’m a Native Vermonter,” or “I was born here,” or “My family’s been here for six generations . . . and we never did it this way before.”

Sometimes, candidates for elected office will tout that they’re native Vermonters, as if that makes them especially qualified for an elected job. Claiming nativity ought to be no more than a compliment to the woman who was in-state at the moment of a Vermonter’s birth, but it has become code-word for Xenophobia – fear of the foreign.

I grant that some of the resentment against newcomers is warranted, and I don’t have patience with people who move here and then complain that there’s no Starbucks nearby. Nor do I have patience with flatlanders who don’t understand – and accept – that in addition to winter, summer and foliage, we also have seasons for sugar, mud, blackflies, and hunting. But I think we do a disservice to the many people who choose to live in Vermont when we give special value to those who were born here over those who immigrated from away.

I’m not a native. I was born in mid-state New York, raised in northern New Jersey, lived in Connecticut as a teen, attended college in Ohio, and spent six years in Manhattan before I moved to Vermont. I’ve now lived here for over half of my life. But I wasn’t born here; I’ll never be a native Vermonter.

I’m not a native. I was born in mid-state New York, raised in northern New Jersey, lived in Connecticut as a teen, attended college in Ohio, and spent six years in Manhattan before I moved to Vermont. I’ve now lived here for over half of my life. But I wasn’t born here; I’ll never be a native Vermonter.

Instead, I’m a Vermonter by choice. My being here is no mere accident of birth. I had to overcome some obstacles to make the move. I had to buy a car, for one, and I had to endure my family’s disbelief for another. The thought of living without pavement or home delivery of the New York Times confounded their sense of order in the universe.

Typically, newcomers either adjust or leave.

Me? I’ve learned to split kindling and to survive without electricity when the power goes out. For me, moving to Vermont feels like coming home.

A significant number of Vermonters weren’t born here, and many of them have made great contributions to our wonderful state, not just in politics, but also in the arts, in industry and innovation, and even in the renaissance of small-scale, value-added agriculture. So I’ll be profiling Vermonters by Choice on occasion.

Meanwhile, we should keep in mind that only the Abenaki are true natives, and they predate Vermont. Even that Connecticut farmer – Vermont’s folk hero Ethan Allen – was from away.

Deborah Lee Luskin is a writer, blogger and pen-for-hire who advances issues through narrative and tells stories to create change.

Glad you are here. I am a 7th generation type. Ancestor was 1st settler in Bennington blah blah. Like your perspective.

Brian, What a kind thing to say! Thank you. As I mentioned above, my grandparents were immigrants to the US, the way I’m an immigrant to Vermont. So migration runs in my family, though I feel as if I’ve put down deep roots in Vermont. The proof, of course, will be if and where my children settle and raise children. We’ll see.

As a seventh-generation Vermonter AND a Vermonter by choice, I agree whole-heartedly 😉

Except for the last paragraph. Putting “true” in front of “native” doesn’t change the meaning to “aboriginal” or “indigenous.” I think people tend to think native means aboriginal because we use the (technically incorrect, in my opinion) term “Native American” to refer to the aboriginal people of North America. But certainly nobody would tell the Irish, for example, that they’re not native Hibernians because their Celtic ancestors were relative late-comers to the island.

Michael, Thank you so much for this comment. I certainly hadn’t thought of “native” v. “aboriginal” – which leads to new questions: What does it mean, then, to say that one is “native” to Vermont – or anywhere, for that matter? How much does it matter where we are born? (Politically, a great deal, and many women come to the US to give birth here, because then their children are “native” (i.e. born) to America. Language becomes like a mirror, reflecting our national turmoil over who has the right to be here, in the one word, “native”. I like the way you describe yourself, as a seventh-generation. (I’m a second-generation American, so I’m awed by people whose families have been here so long.)You have provided great food for thought. Thanks!